How Fasting Works

Simple science, practical takeaways.

Fasting changes more than your eating schedule it changes how your body fuels, repairs, and regulates itself. Here are the key processes explained simply:

Metabolic Switching & Signalling

Circadian Timing (Biological Clock)

Autophagy (Cellular Housekeeping)

Longevity Angles

Weight & Metabolic Health

Details are Given Below

One

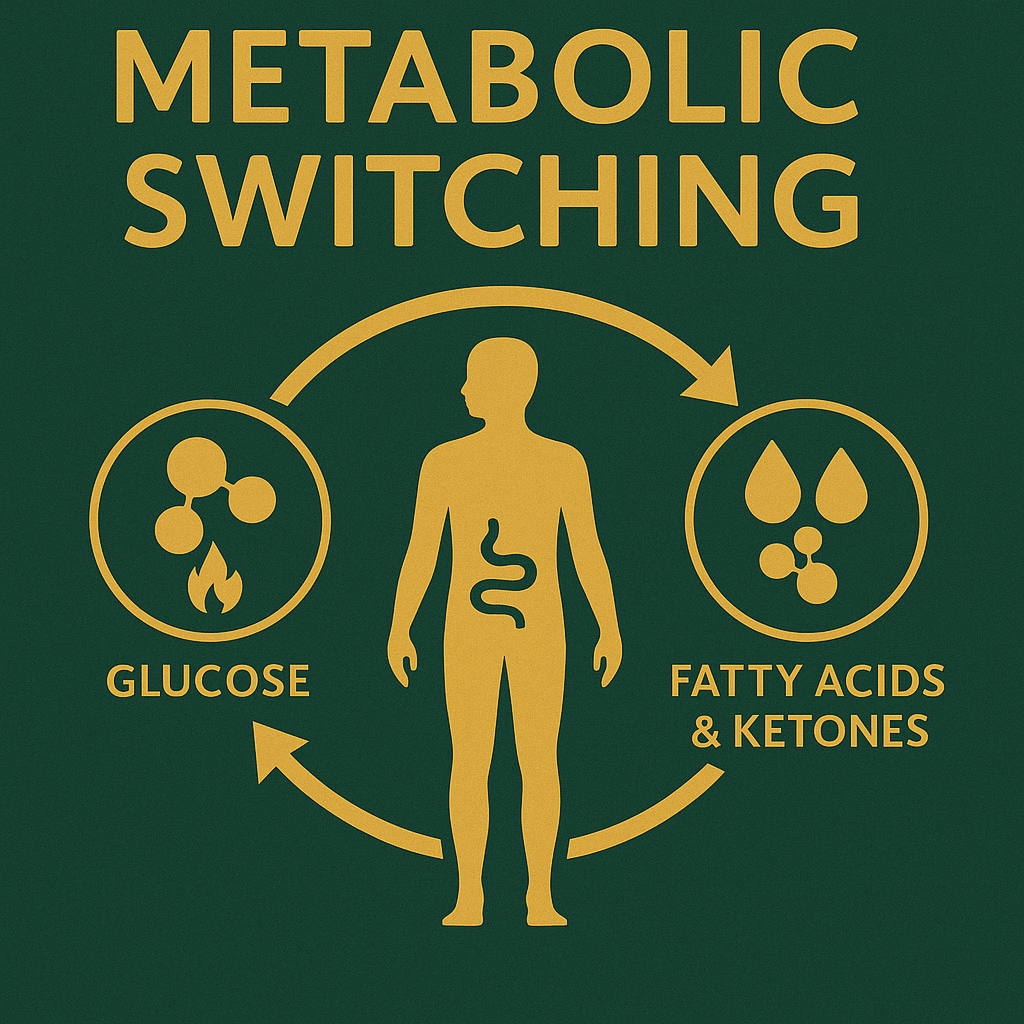

Metabolic Switching & Signalling

When you fast long enough, your body gradually shifts away from burning glucose as its main fuel. Instead, it starts using fatty acids and ketones. This process, often called metabolic switching, activates signalling pathways like AMPK and mTOR, which play roles in energy regulation and repair (Mattson).

What it means for you:

Fasting encourages your body to become more flexible in how it uses energy, which may improve resilience and reduce energy crashes.

Two

Circadian Timing (Biological Clock)

Your body has a natural clock that governs sleep, hormones, and metabolism. Eating in sync with this clock matters. Research by Satchin Panda shows that earlier eating windows—finishing meals earlier in the day—can improve blood sugar control and appetite regulation, even without weight loss.

What it means for you:

Eating earlier in your fasting rhythm may help you feel more balanced and support metabolic health.

Two

Circadian Timing (Biological Clock)

Your body has a natural clock that governs sleep, hormones, and metabolism. Eating in sync with this clock matters. Research by Satchin Panda shows that earlier eating windows—finishing meals earlier in the day—can improve blood sugar control and appetite regulation, even without weight loss.

What it means for you:

Eating earlier in your fasting rhythm may help you feel more balanced and support metabolic health.

Three

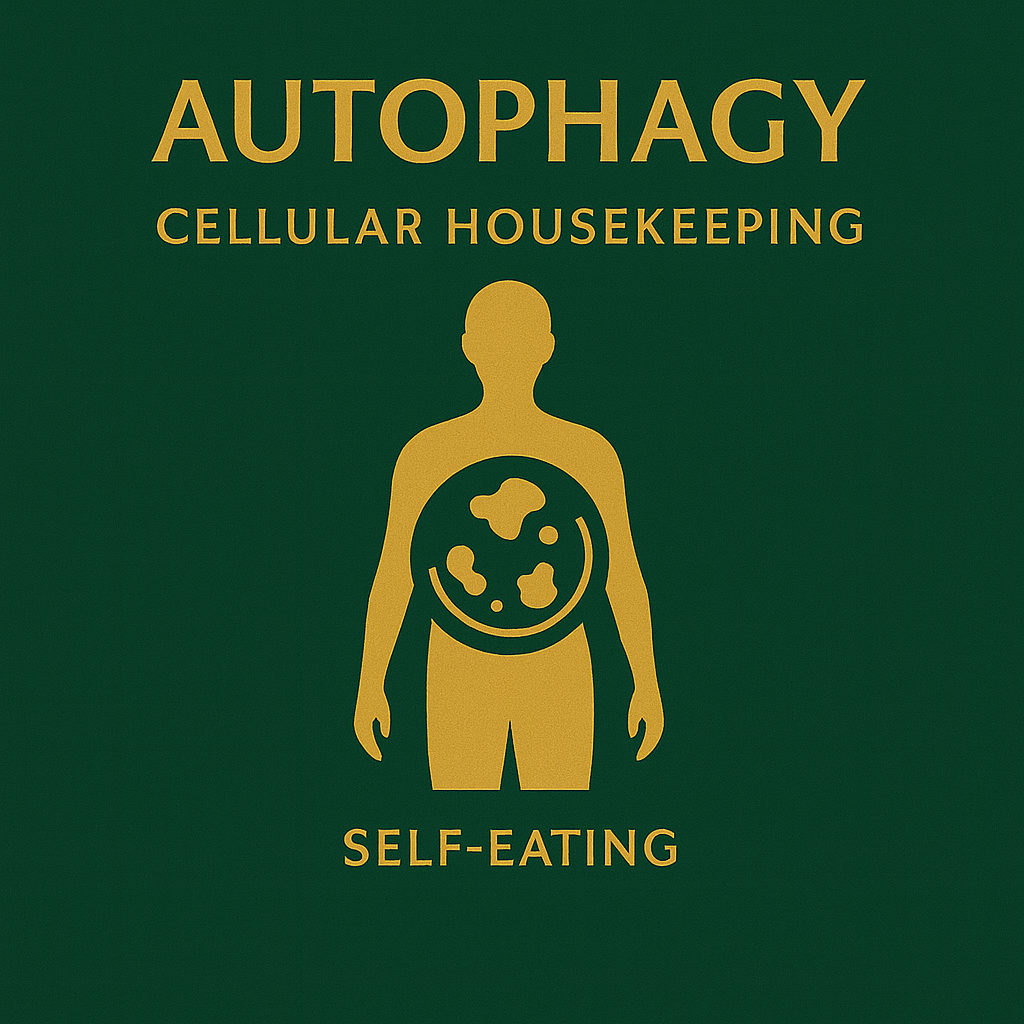

Autophagy (Cellular Housekeeping)

In longer fasts, your cells enter a process called autophagy, which literally means “self-eating.” Damaged proteins and cell components are broken down and recycled. Yoshinori Ohsumi’s Nobel Prize–winning work put autophagy in the spotlight. This process supports cellular repair, resilience, and healthy aging.

What it means for you:

While autophagy is promising for longevity, it’s not a license for extreme fasting. Balance and safety still matter most.

Weight & Metabolic Health

Four

Large studies comparing intermittent fasting with continuous calorie restriction often show similar weight-loss results. The biggest factor isn’t the method—it’s sustainability. Individual responses vary widely. What truly matters is finding an approach you can stick with long term.

What it means for you:

The “best” fasting protocol is the one you can keep doing while maintaining food quality, sleep, and lifestyle balance.

Four

Weight & Metabolic Health

Large studies comparing intermittent fasting with continuous calorie restriction often show similar weight-loss results. The biggest factor isn’t the method—it’s sustainability. Individual responses vary widely. What truly matters is finding an approach you can stick with long term.

What it means for you:

The “best” fasting protocol is the one you can keep doing while maintaining food quality, sleep, and lifestyle balance.

Five

Longevity Angles

Valter Longo’s Fasting-Mimicking Diet (FMD) explores periodic fasting designed to trigger healthy-ageing biomarkers. It’s an exciting area of research, but it’s a specialist protocol—not suitable for everyone. Always approach it with guidance and medical oversight.

What it means for you:

Fasting may support long-term health, but daily habits and safety should always come first.

The Fasting Treasure No where to found

Chrono-Fasting: Why Earlier Eating Windows Often Work Better

Your metabolism runs on a clock. Insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance are highest earlier in the day; melatonin at night impairs insulin secretion. Eating late pushes calories into a metabolically unfavorable window. Early time-restricted eating (eTRE) exploits this by finishing meals earlier—often improving biomarkers independent of weight change.

The circadian argument

Pancreas & peripheral clocks. The pancreas anticipates morning feeding with better insulin output; skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity falls across the day.

Nighttime mismatch. Late eating coincides with melatonin, which blunts insulin secretion, raising post-meal glucose. Chronically, this pattern associates with higher HbA1c and triglycerides.

Human trials

In men with prediabetes, eating within 8 am–2 pm for five weeks (same calories as control) improved insulin sensitivity, lowered blood pressure, and reduced oxidative stress. Other eTRE trials report better 24-hour glucose profiles and appetite regulation. Notably, these changes arise without weight loss, a pure timing effect.

Practical eTRE

Pick an 8–10 h window ending by 3–6 pm. Examples: 8–4 pm or 10–6 pm.

Front-load protein. A protein-forward breakfast (25–40 g) stabilizes appetite and glucose.

Move post-meal. Walks amplify glycemic benefits.

Make it social. If dinners are non-negotiable, compromise with a 10-h window (e.g., 10–8) and avoid late-night snacking.

Who benefits most?

People with insulin resistance, hypertension, fatty liver, or poor sleep. Night-shift workers require tailored strategies (e.g., consistent “day” on their schedule, compression of meals in their wake cycle).

Bottom line:

Aligning when you eat with how your body handles nutrients makes the same calories “metabolically cheaper.” If you can swing it, earlier windows provide extra leverage.

Selected references

Sutton EF et al. Early TRE improves insulin/BP. Cell Metab. 2018;27:1212–1221.e3.

Longo VD, Panda S. Cell Metab. 2016;23:1048–1059.

Jamshed H et al. Early vs mid-day TRE. Nutrients. 2019;11:1234.

What’s Next Step

Explore our Beginner’s Guide or download the 14-Day Plan to start applying these principles safely in your daily life.

COMPANY

Keep in Touch

Copyrights 2025 | Terms & Conditions

Disclaimer: The information available is for informational purpose only and not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.